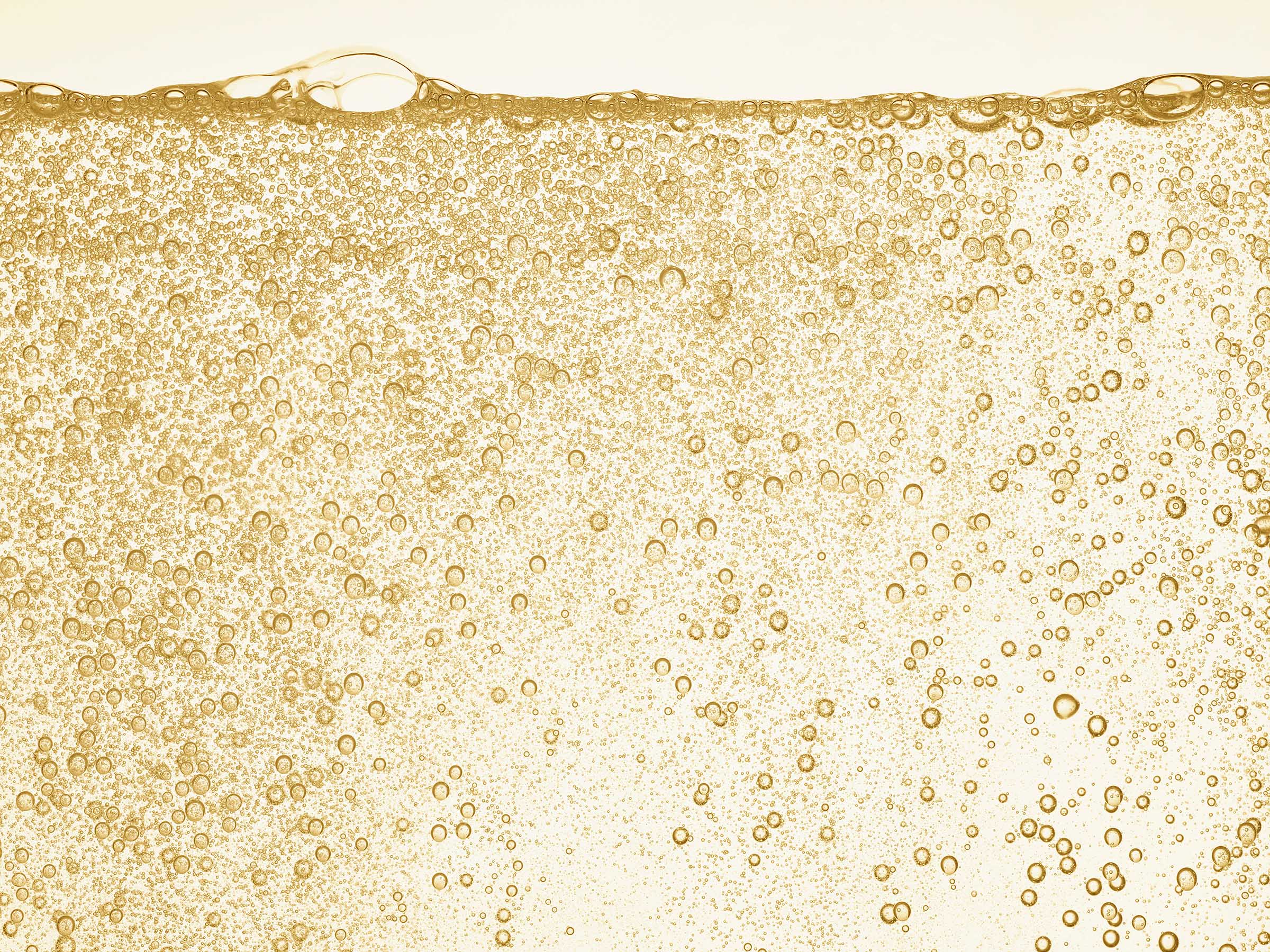

Champagne is a really exquisite beverage, and the way it bubbles is one of the things that contributes to its elegance. Researchers have been puzzling about why the beverage bubbles the way it does, with those bubbles often growing in straight lines, for years. A recent study claims to have finally figured out the chemistry of champagne bubbles and what causes them to increase so beautifully.

We all know how carbonated beverages work: bubbles form in the liquid and rise quickly to the top. When the bubbles in carbonated water explode like fireworks in the night sky, we may observe it. Beer exhibits the same behaviour when the bubbles clump together and disperse throughout the liquid. Champagne has always been a little different. It pops up in a series of straight lines, almost like an assembly line, as opposed to clumping up or taking off.

The scientists also discovered that you can control the motion of the bubbles by varying the amount of surfactants present in the liquid. Researchers now have answers as to why this happens thanks to this recent study. Understanding the chemistry underlying champagne bubbles may seem ridiculous, but researchers claim that doing so may help us better understand how bubbles function in places like those near deep-sea vents.

The increasing amount of soap-like components in champagne, according to the current study, is what causes the bubbles in champagne to respond by rising. These compounds are known as surfactants, which are lipids that also contribute to the deliciousness of champagne, according to Science Alert.

Understanding the physics of champagne bubbles is a fun topic for a blog. There are several reasons why this kind of research study is important, as I noted above. Not only does it answer a puzzling question that has perplexed scholars for a while, but understanding why champagne bubbles in the manner it does can also help us understand why other substances bubble in the manner they do.

I pointed out the above-mentioned deep-sea vents, which frequently spew methane bubbles into the water and make it risky to approach so that they can get samples. By seeing how the bubbles travel, they may be able to determine the surfactant levels using this research study without the need to take direct samples. This method might also be used to maintain track of the tanks in water treatment systems, among other things.

A study published in Physical Review Fluids describes the conclusions of the research into the science of champagne bubbles.